We formed a small group of interested emergency physicians (both senior residents and attending emergency physicians interested in global health to create a 3-month introductory seminar on the specialty of Emergency Medicine to be given to senior medical students in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Since Emergency Medicine is not a developed specialty in Cambodia, we reached out to the Dean of the University of Puthisastra Medical School about developing the course and presenting it as an elective for their senior medical students. We have worked with the Dean’s office to create a course that meets their accreditation standards (similar to ACGME) that will include 29 webinar sessions (each scheduled for 1 ½ hours) which will follow the recommendations of the Clerkship Directors of Emergency Medicine (CDEM) medical student curriculum. The course will begin on September 4, 2025, and run through Nov 19, 2025 and will be given on Mondays, Wednesday, and Fridays at 9 AM (Cambodian time).

This grant proposal is to support our 3 day capstone project where we (myself and two senior residents) will travel to Phnom Penh, to work with the students in-person and teach clinical skills and work with the students on patient interactions using an OSCE format where junior medical students from the University of Puthisastra medical school will act out classic presentations of Emergency Medicine chief complaints. On the third day, their learning will be assessed both through a written final exam (40% of their grade) and an OSCE evaluation (60% of their grade). We will also be gathering data on the student’s learning experience to provide feedback for the next iteration of the course.

Although the attendings and residents associated with the project are from Harbor-UCLA, it is an individual project that is not being sponsored by the medical center or university. In addition, the residents and attending involved will be using their own vacation time to teach and travel to Phnom Penh.

As Emergency Medicine is not a developed specialty in Cambodia, this course will provide medical students with early exposure to the specialty and help equip them to manage patients with life-threatening or urgent conditions. In the 1970s Cambodia experienced a genocide and war that lasted until the early 1990s and the country is still recovering from that tumultuous period. The healthcare system in Cambodia is still undergoing reform and based on my review only one large public university provides postgraduate training in critical care medicine. In an observational study of adults seeking emergency care at two public hospitals in Cambodia, researchers found a high admission-to-death ratio and limited application of diagnostic techniques. Additionally, a cross-sectional survey assessing the capacity of the Cambodian emergency care system highlighted education as a key factor in bridging performance gaps. As such, educational interventions represent a critical area for growth and development of emergency and critical care medicine in Cambodia.

Our goal is to improve participants’ confidence and competence in caring for critically ill patients. The curriculum is designed to build foundational knowledge and practical skills in five key areas:

I. Foundational knowledge of Emergency Medicine

II. Initial approach to the emergency patient

III. Diagnostic testing and interpretation

IV. Emergency stabilization and resuscitation

V. Emergency procedures.

To ensure the course addresses local needs, I am developing a needs assessment to identify knowledge gaps, available resources, and how we can best support the students. The hands-on procedural training during the capstone visit will be a critical component to their critical care education. In partnership with their Dean’s Office, we will assess learner outcomes through written evaluations and OSCEs during the in-person portion. These will be compared to baseline data collected via a pre-course survey.

Using student feedback, assessment results, and overall learner experience, we will revise and adapt this curriculum in collaboration with our partners at the University of Puthisastra. This pilot serves as the foundation as we develop a reproducible model that we hope will eventually be led by local faculty to ensure sustainable growth and long-term impact.

Introduction

Providing global health equity is a driving concern in emergency medicine, but many countries around the world still do not recognize Emergency Medicine as a specialty and often employ general practice practitioners in their emergency rooms. In 2019, the World Health Organization Assembly passed resolution 72.16 recognizing Emergency Care as an essential health service.

Employing recommendations published by the Clerkship Directors in Emergency Medicine (CDEM) for teaching emergency medicine to medical students in the United States, we developed a curriculum to introduce the specialty of emergency medicine to a group of senior medical students at a private medical school in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Utilizing planned learning objectives, we divided the curriculum into 28 ninety-minute webinars covering the breadth of emergency medicine topics and concluded the course with a 3 day in-person teaching and assessment session focusing on hands-on simulation and objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) style teaching.

Background

As emergency physicians, we care for all patients regardless of their presentation, socioeconomic status, or ability to pay. Since the beginnings of emergency medicine specialty training in the 1970s, there are now estimated to be over 130,000 trained emergency physicians around the world. Despite this, there are many countries who have yet to appreciate and recognize the unique services that emergency medicine can provide to their health systems.

In Southeast Asia, Singapore was one of the first to recognize EM as a specialty as early as 1984, Malaysia in 2002, Thailand in 2003, Vietnam in 2010, Laos in 2017. Cambodia, however, has yet to recognize emergency medicine as a specialty. Literature from Cambodia has identified this as a major public health concern, 2022 with a cross-sectional survey assessing the capacity of the Cambodian emergency care system highlighting education as a key factor in bridging performance gaps. Our goal was to pilot a short course “An Introduction to Emergency Medicine” to spark interest in Emergency Medicine and potentially open the door for the development of Emergency Medicine as an organized specialty in the Cambodian health care system.

Educational Objectives:

To pilot an introduction to emergency medicine course for 6th year medical students at a private medical university in Phnom Penh where emergency medicine is not considered a specialty and there is no specialty training available.

Curricular Design:

One of the authors had previous experience working with medical students at another private medical university in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Using contacts from former students and current friends who live in Cambodia, the Dean of this private medical university in Phnom Penh was contacted, and the author made a proposal to create a course as a charitable outreach to teach an “introduction to Emergency Medicine” to their 6th year medical students. After obtaining permission from their University President, our team worked in collaboration with their Dean’s office to create and deliver the course. For the in-person sessions, the school provided an auditorium, procedural simulation devices, junior medical students to act as simulated patients, and all the resources we needed to give an effective presentation.

Although not innovative in terms of the emergency medicine topics delivered, our team developed 29 presentations based on these topics, to deliver to a class of 6th year medical students, which in Cambodia equates to 2nd or early 3rd year medical students in our system. (Cambodia uses the French system of medical education where students begin medical school after completing high school and students are taught in English as the primary teaching language).

Basing our education methods on ones that are currently employed at our large teaching hospital in the United States, we tried to gather information from the Cambodian medical students on their interests and learning styles and used anonymous pre-course, mid-course, and end-of-course surveys to obtain feedback, as well as asking for feedback at the end of each webinar.

For the webinar sessions, we started with the recommended course topics found on the Society of Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) CDEM website for 3rd and 4th medical students in the US (https://www.saem.org/about-saem/academies-interest-groups-affiliates2/cdem/for-students/online-education/m3-curriculum and https://www.saem.org/about-saem/academies-interest-groups-affiliates2/cdem/for-students/online-education/m4-curriculum) and developed 29 webinars which we delivered Monday, Wednesday, and Friday over the course of 10 weeks, with each webinar lasting from 90 – 120 minutes covering the core concepts of emergency medicine.

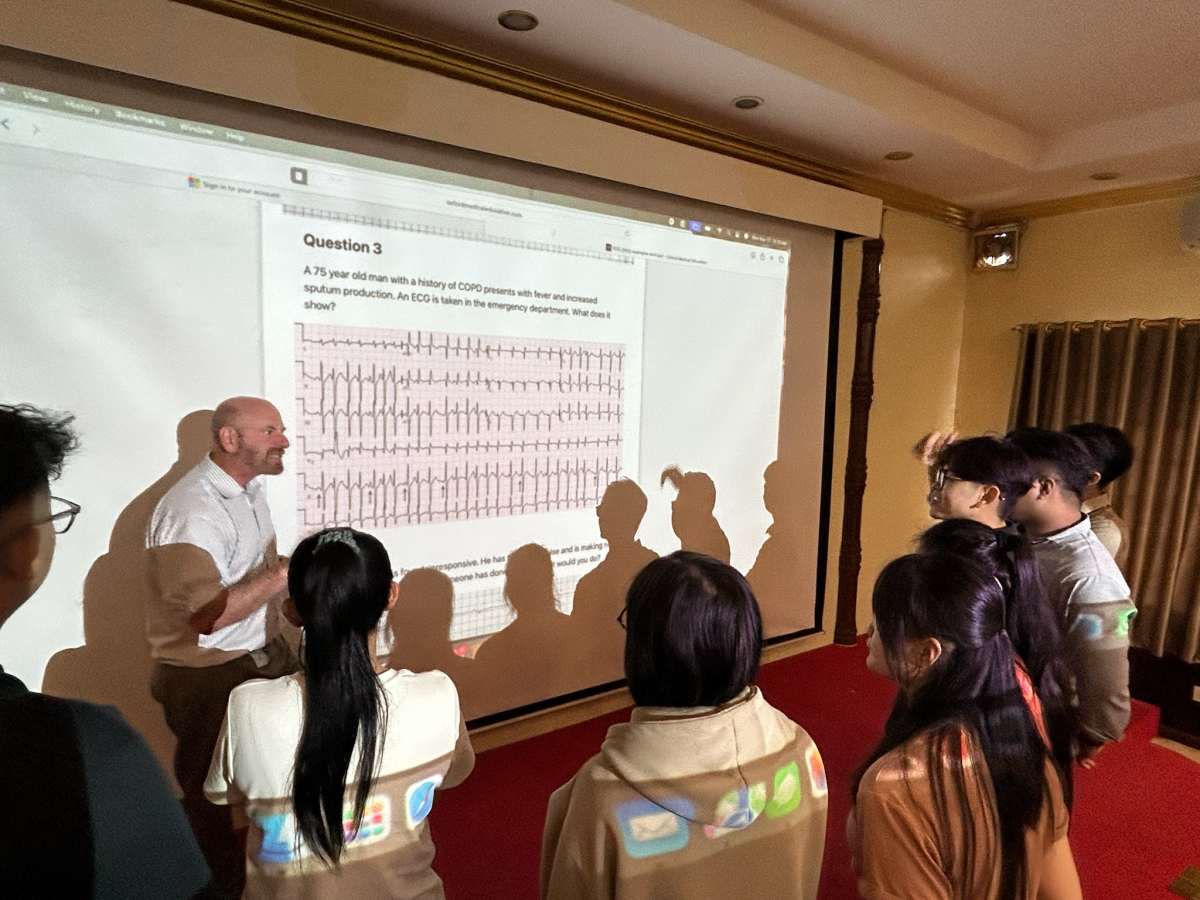

After the webinars were concluded, we conducted a 3 day in-person teaching session based on US style teaching techniques for 3rd and 4th year medical students that included procedural simulation and OSCE style simulated patient presentations. We concluded with a written multiple-choice test of 100 questions and a direct observation (OSCE) of a simulated patient encounter where we utilized junior medical students (3rd year) who were instructed on how to simulate the patient prior to performance of the cases.

Impact/Effectiveness: As a pilot project, this introduction to emergency medicine course was well received by the students and by the faculty at the medical school. We had 38 students (about 60 percent of the class) participate on a voluntary basis during their school break when they were studying for their national exams. All students passed the multiple-choice test and OSCE simulated patient scenario. Feedback from their Deans was positive as well and, we were asked to continue the course as an annual offering for the students. About 40% percent of the students provided anonymous feedback which we will incorporate into future courses (e.g. they wanted homework assignments, group projects, and to spread out the course over a longer period of time). There was also discussion about whether the course would be better suited for 7th and 8th year students (similar to our 3rd and 4th year medical students) who would have had more clinical experience. We would also like to expand the educational opportunity to the other medical schools in Phnom Penh and have already made progress to include the other private medical university for next year.