During a three-week global health rotation, I will collaborate with clinicians and educators at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC) in Moshi in northern Tanzania and Ilula Lutheran Hospital (ILH) in southern Tanzania. The purpose of this trip is to strengthen cancer care and education through bidirectional learning, curriculum refinement, and supervised clinical engagement.

Midway through my internal medicine training, I redirected my career toward primary care with a focus on cancer prevention. This decision was shaped by personal loss —my father’s death from liver cancer after decades of undiagnosed chronic hepatitis B— and professional experiences in cancer research and registry development in the United States. These experiences highlighted that despite advances in oncologic therapies, outcomes are often determined long before diagnosis as many cancers are preventable.

While in Tanzania, I will collaborate with faculty at KCMC to update a cancer care course initially developed in 2021, incorporating recent local initiatives and emphasizing prevention, screening, diagnosis pathways, treatment considerations, and palliative care in low-resource settings. I will also assist with coordination and educational support for a long-standing international healthcare conference in Ilula, involving clinicians from southern Tanzania and international partners. In addition, I will serve as a volunteer clinician at ILH, participating in inpatient wards, outpatient clinics, mobile clinics, and palliative care home visits under local supervision.

The primary beneficiaries of this project are patients and communities in northern and southern Tanzania who face limited access to cancer prevention services, early screening, and timely diagnosis.

Local physicians, nurses, and trainees at KCMC and ILH also benefit directly from this collaboration through shared clinical learning and strengthened educational frameworks. By reinforcing prevention-focused primary care and cancer awareness, the project supports safer, earlier intervention for patients while building sustainable local capacity.

This experience will also inform my future work caring for immigrant and working-class populations in Minneapolis, MN, many of whom originate from regions with similar cancer epidemiology and structural barriers to care.

In the short term, this project will support improved cancer-related education and clinical awareness through updated curricular materials, conference participation, and direct patient care. Measurable outcomes include completion of revised educational content at KCMC, participation in interdisciplinary educational sessions in Iringa, and supervised clinical engagement across inpatient, outpatient, and community settings.

The long-term impact lies in capacity strengthening and sustainability. Updated teaching materials and strengthened professional relationships will support ongoing education in cancer care beyond the duration of the rotation. Knowledge exchanged during clinical and educational activities will reinforce locally driven, adaptable prevention and screening strategies.

For my professional development, this experience represents a foundational step toward a career in primary care with a focus on cancer prevention. Upon return, I plan to share insights through teaching and discussion within my training program, extending the benefits of this experience beyond a single trip and fostering continued advocacy for cancer prevention and health equity.

Post-Trip Recap: Tanzania Global Health Rotation

During my global health rotation in Tanzania, I worked across two distinct healthcare settings: the Cancer Care Center at Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre (KCMC), a zonal referral hospital in northern Tanzania, and Ilula Lutheran Hospital, a district hospital currently transitioning toward regional referral status. Experiencing care delivery at both sites offered a grounded view of cancer prevention and management across different levels of the health system.

At KCMC, I observed cancer care at the highest referral level available in the region. While the resources and subspecialty access differed from district-level care, many challenges were shared across both sites. Patients often presented late in the course of disease, constrained by financial limitations, transportation barriers, and geographic distance. Diagnostic delays and limited treatment options were common, reinforcing how much cancer outcomes are shaped long before patients reach tertiary care.

During my time at the KCMC Cancer Care Center, I participated in the inaugural Oncology Research Unit meeting, the first of what is planned to be a monthly forum for academic discussion and collaboration. I also engaged with oncology staff regarding recent developments in cancer care, including the opening of a radiation therapy center with plans to treat its first patient in February 2026. These advances represent meaningful progress in expanding access to cancer treatment in northern Tanzania.

Cancer prevention was a central focus of my learning at KCMC. I learned that esophageal cancer is the third most common cancer in Tanzania and that the country lies within the “esophageal cancer belt” of Africa. Upon returning to the United States, a preliminary review of our cancer registry revealed that squamous cell carcinoma was the most common esophageal cancer among Black patients, with many patients born in East Africa. This overlap highlighted a disparity that merits further study and underscored the importance of culturally informed prevention and screening strategies.

At Ilula Lutheran Hospital, I worked alongside Tanzanian colleagues in inpatient wards, outpatient clinics, and palliative care home visits. The clinical burden included lower respiratory tract infections, malaria, newly diagnosed HIV infections, and a high prevalence of Helicobacter pylori, with approximately 63% of tested patients screening positive. HIV care was widely accessible through government-subsidized programs, illustrating how policy-level investment can meaningfully expand access to lifesaving treatment.

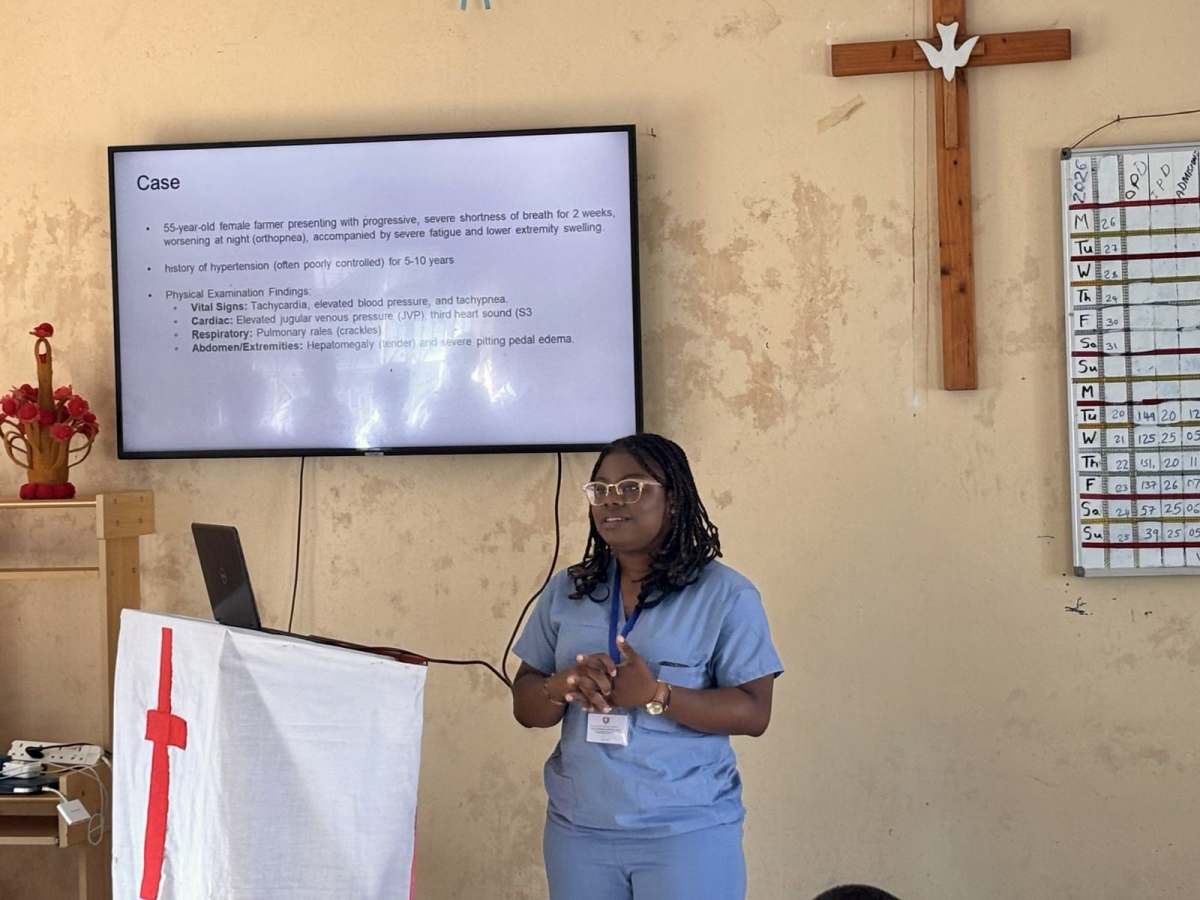

In addition to clinical care, I delivered a lecture on heart failure and its management, a condition associated with high one-year mortality following hospitalization in Tanzania. Informal bedside discussions often expanded into broader conversations on cancer prevention, including treatment of H. pylori to reduce gastric cancer risk, cervical cancer screening in young women (the leading cancer in Tanzania), treatment of schistosomiasis to prevent liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, and colon cancer screening in older adults presenting with anemia.

The rotation concluded with a two-day conference focused on quality improvement initiatives and obstetric care, bringing together clinicians from across southern Tanzania. The exchange of ideas reinforced the power of regional collaboration and shared learning.

This experience deepened my commitment to primary care with a focus on cancer prevention. Learning from Tanzanian clinicians—who consistently adapt and innovate within constrained systems—will directly inform how I approach prevention, screening, and patient education in my future practice, particularly among immigrant and underserved populations.

I am deeply grateful to the Doximity Foundation for making this experience possible and for supporting global health work that emphasizes education, partnership, and long-term impact.